A new wave of watchmakers are moving away from genderising their watches, a small but significant step towards a more inclusive community.

A new wave of watchmakers are moving away from genderising their watches, a small but significant step towards a more inclusive community.

We present a paradox as an opener: wristwatches were originally designed and worn by women, while men were happy to indulge in their pocket watches. Fast-forward to the present day, and watches — as they are termed these days — are marketed by default as hyper-masculine accessories for men, while women’s options were relegated to the sidelines. A further underlying narrative festering over the decades — men should not wear dainty or diamond watches while women should stick to watches below 34mm — complicates matters more.

For decades, some of horology’s most iconic models were designed for men, while women’s watches were simply either downsized, blinged out, or worse, quartz variants of the more complex mechanical movements. Watch manufactures took a while, but later realised the importance of the female clientele that saw — in the recent decades— a rise of original creations catered to them. Could such a move have been implemented in the earlier decades? No. Because society was not ready back then. Shifts in society’s understanding and acceptance of gender have seen an increasing number of watch manufactures making inroads to a more inclusive approach — by removing gender tags altogether.

One of the biggest catalysts for such a move lies undoubtedly in the fashion world, as luxury houses push, bend and break the rules and boundaries with their creations. There has been a knock-on effect trickling into both the jewellery and watch industries; however, given how traditional the latter is, one begins to grasp why such changes only happened a few years ago. Funny enough, one of the early vanguards to ditch gendering watches was not a watch brand but a platform seller. Pre-owned seller Watchfinder & Co. removed gender labels for its watches in2021 and has instead categorised them as small, medium or large.

“By removing the men’s and women’s categories from our business, we are encouraging customers to explore and discover more watches, helping them find the right watch for them. With a large proportion of men’s watches getting smaller and women’s watches getting bigger, we feel that gender categories are now obsolete,” says Matt Bowling, co-founder of Watchfinder & Co., in 2021.

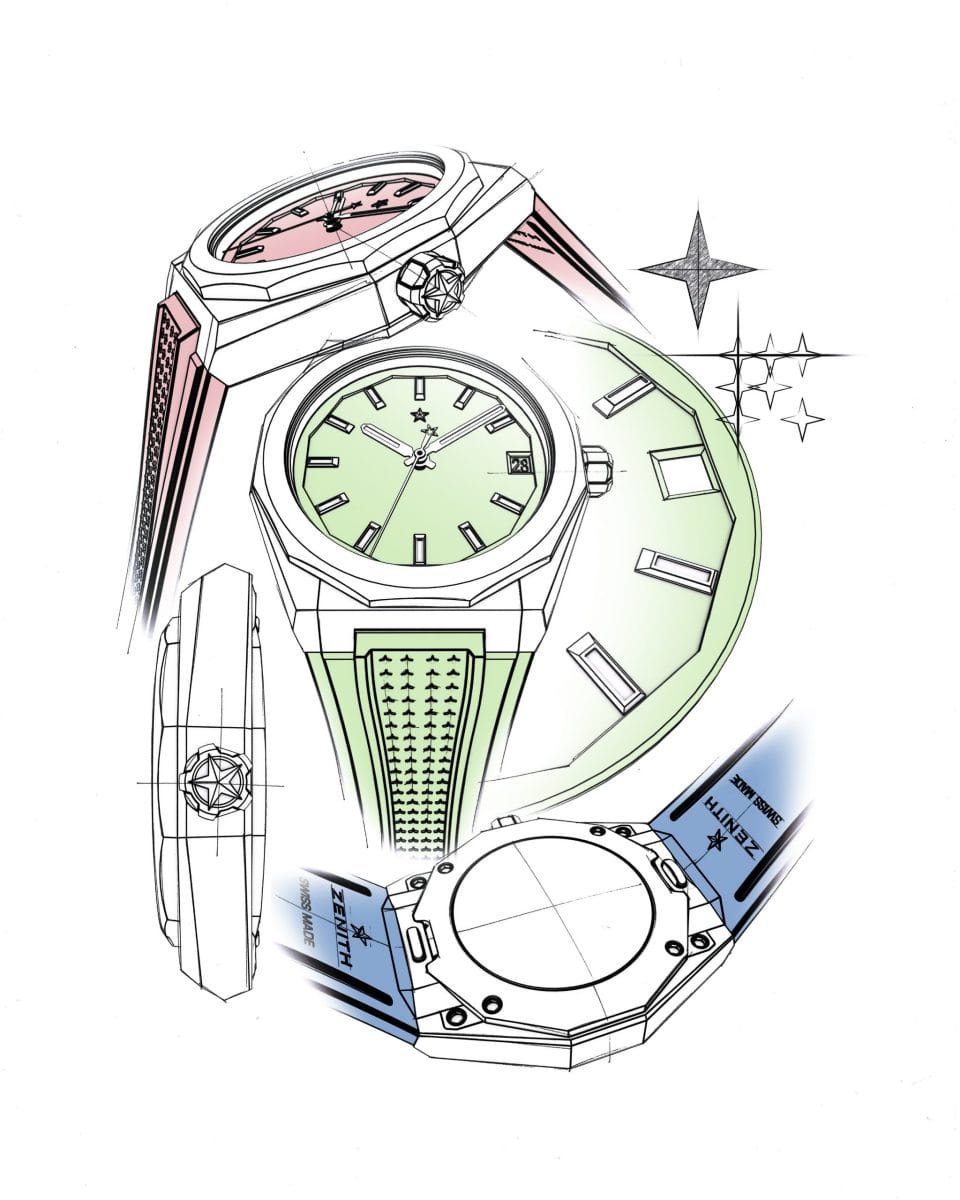

That idea resonated with a few watch manufactures. Zenith went ahead and ditched gender categories under then-CEO Julien Tornare’s tenure. “I would say it’s a logical step for a brand that wants to be contemporary. We’re living in the 21st century, launching modern products, so in today’s world, who are we to say this watch is for a male or female? It doesn’t make sense,”shares Tornare in an interview with Men’s Folio in 2022. “We make beautiful watches in different sizes; some have a feminine touch while some have a masculine touch. Men can have a feminine touch and vice versa. We’re in a world today where we should not make separation by gender; that’s part of the past. I always use cars as an example. 30 years ago, we would hear that these cars were for men and those were for women. Today, who would ever say that? In watches, I believe we are the first to remove gender tags, and I’m very happy about it because I think that’s the future.”

That idea resonated with a few watch manufactures. Zenith went ahead and ditched gender categories under then-CEO Julien Tornare’s tenure. “I would say it’s a logical step for a brand that wants to be contemporary. We’re living in the 21st century, launching modern products, so in today’s world, who are we to say this watch is for a male or female? It doesn’t make sense,”shares Tornare in an interview with Men’s Folio in 2022. “We make beautiful watches in different sizes; some have a feminine touch while some have a masculine touch. Men can have a feminine touch and vice versa. We’re in a world today where we should not make separation by gender; that’s part of the past. I always use cars as an example. 30 years ago, we would hear that these cars were for men and those were for women. Today, who would ever say that? In watches, I believe we are the first to remove gender tags, and I’m very happy about it because I think that’s the future.”

Bowling made a fair point. For a period, men were gravitating towards larger dimensions, a phenomenon sparked by Sylvester Stallone and his love for (large) Panerai and Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak Offshore paved the way for the likes of Hublot and Richard Mille to produce watches well into the 44mm diameter and beyond. Hip hop helped ensure men’s watches stayed large with the likes of Jay Z, Sean “Diddy” Combs and 50 Cent popularising supersized watches. Conversely, women’s watches were getting smaller as a sign of femininity and elegance. Rolex’s Lady-Datejust — released in 1957 — set the standard for women’s watch dimensions at 26mm. Chanel dipped the scale further when their Première debuted at roughly 20mm, and all these were happening while key players such as Jaeger-LeCoultre, Cartier and Bvlgari were already operating within that range of dimensions.

All seemed well until one fine day when men and women had enough of being told what toor not to wear or being ushered to the correct vitrines when browsing in luxury boutiques.

It was no surprise that women were the ones who defied those expectations. Climbing the corporate ladder and wanting to be taken seriously in boardroom meetings meant donning larger watches. That caught on and became a trend soon after; (Rolex) Submariners (Panerai) Luminors — to name a few — became a common sight on ladies’ wrists. Not long after, watch manufactures were ditching their small blueprints in favour of larger ones to cater for the shift in consumption taste and habits before women wearing large watches was properly normalised in the last 10 years or so.

On the flip side, there was greater inertia moving towards smaller watches among men. The vintage watch boom was a great push as the idea of elegance, subtlety or being discreet would only work for smaller watch dimensions. Then came the femme movement, as such clothes and accessories caught on with modern-day men. The unshakeable notion that small or feminine watches are not for men began to waver and ultimately crumbled as this generation’s celebrities and influencers wielded their influence. Timothée Chalamet, Bad Bunny, and Austin Butler were spotted donning petite watches on both the red carpet and coffee runs, and those are just three of the many others who have hopped onto the bandwagon. Small and mid-sized Cartier Tanks and Jaeger-LeCoultre Reversos became perennial favourites and experienced a surge in interest. Precious stones were thrown into the mix, too, as men got comfortable with diamond or gem-set watches

On the flip side, there was greater inertia moving towards smaller watches among men. The vintage watch boom was a great push as the idea of elegance, subtlety or being discreet would only work for smaller watch dimensions. Then came the femme movement, as such clothes and accessories caught on with modern-day men. The unshakeable notion that small or feminine watches are not for men began to waver and ultimately crumbled as this generation’s celebrities and influencers wielded their influence. Timothée Chalamet, Bad Bunny, and Austin Butler were spotted donning petite watches on both the red carpet and coffee runs, and those are just three of the many others who have hopped onto the bandwagon. Small and mid-sized Cartier Tanks and Jaeger-LeCoultre Reversos became perennial favourites and experienced a surge in interest. Precious stones were thrown into the mix, too, as men got comfortable with diamond or gem-set watches

Naturally, watchmakers had to adapt, which meant downsizing their male-centric offerings, even those considered core pieces. 39mm to 41mm diameter were palatable and modest by their books, though anything drastically smaller would fall under women’s categories.

Cartier, Audemars Piguet, Girard-Perregaux, and Hublot came up with various solutions to address this, such as producing watches in an assortment of sizes. For instance, Cartier’s Tank and Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak watches are produced in categories of small, medium, large and extra large, while Girard-Perregaux’s Laureato and Hublot’s Classic Fusion are produced and sorted by diameters from 36mm onwards.

Marketing departments were the next to catch on as advertising campaigns, messaging and visuals underwent upheaval. IWC Schaffhausen’s infamous and chauvinistic “Engineered for Men”advertising campaign in the early 2000s was eventually canned; women were later advertised wearing the same watches as their male counterpart, the latest being IWC brand ambassador Eileen Gu flaunting the 44.5mm IWC Pilot’s Watch Chronograph Top Gun Edition“Lake Tahoe” just as Rami Malek wore the same Tank Française watch as Catherine Denevue in last year’s Cartier campaign.

Marketing departments were the next to catch on as advertising campaigns, messaging and visuals underwent upheaval. IWC Schaffhausen’s infamous and chauvinistic “Engineered for Men”advertising campaign in the early 2000s was eventually canned; women were later advertised wearing the same watches as their male counterpart, the latest being IWC brand ambassador Eileen Gu flaunting the 44.5mm IWC Pilot’s Watch Chronograph Top Gun Edition“Lake Tahoe” just as Rami Malek wore the same Tank Française watch as Catherine Denevue in last year’s Cartier campaign.

While the list of brands which removed gender categories are still considerably small at the moment, the slowly growing list brings assurance that one of the most traditional industries is taking heed and moving in the right direction. Having big names from Richemont, LVMH and other privately own manufactures will definitely aid this cause. CEOs already recognise the fact that they cannot dictate what a client purchases and neither should we. Watches are designed genderless but ultimately fell victim to genderisation. As society moves towards greater inclusivity, perhaps removing gender labels is the least that can be done to make the watch community more inclusive.

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our April 2024 issue.