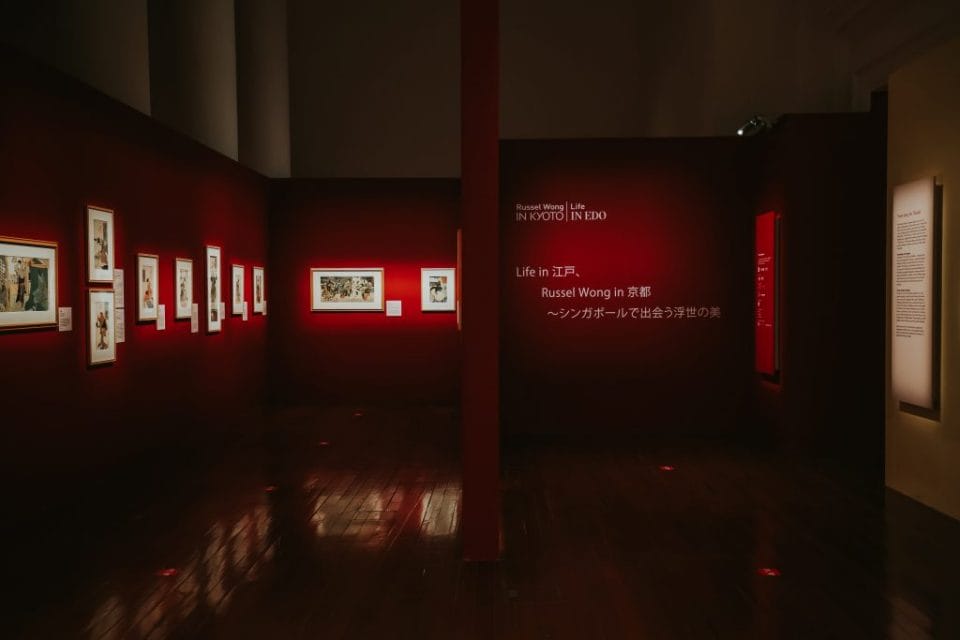

To my best knowledge, this is the first ever large-scale ukiyo-e exhibition in Singapore and ACM is very pleased to present “Life in Edo | Russel Wong in Kyoto” to our audience. Images of ukiyo-e prints and paintings are so popular internationally. Famous prints like Hokusai’s “Great Wave Off the Coast of Kanagawa” and “Mild Breeze on a Fine Day” (also known as “Red Fuji”) could be seen everywhere — even outside of Japan — and they were depicted in various types of merchandise.

Their impact could be compared to other global icons such as Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” or Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers”.

—

One of the most difficult parts was to find the link to connect between the two different sections – lifestyles and trends in Edo-period Japan and the geiko/maiko community in Kyoto today, and the link between two different mediums – woodblock prints and contemporary photography.

Yoasobi’s Gunjou : a recent ear candy and a popular duo group in Japan whose songs are all based on short stories posted on the Monogatary website operated by Song Music Japan. Catchy melody with encouraging and poetic lyrics bring me adrenaline and positivity during the installation phase of the “Life in Edo | Russel Wong in Kyoto”.

—

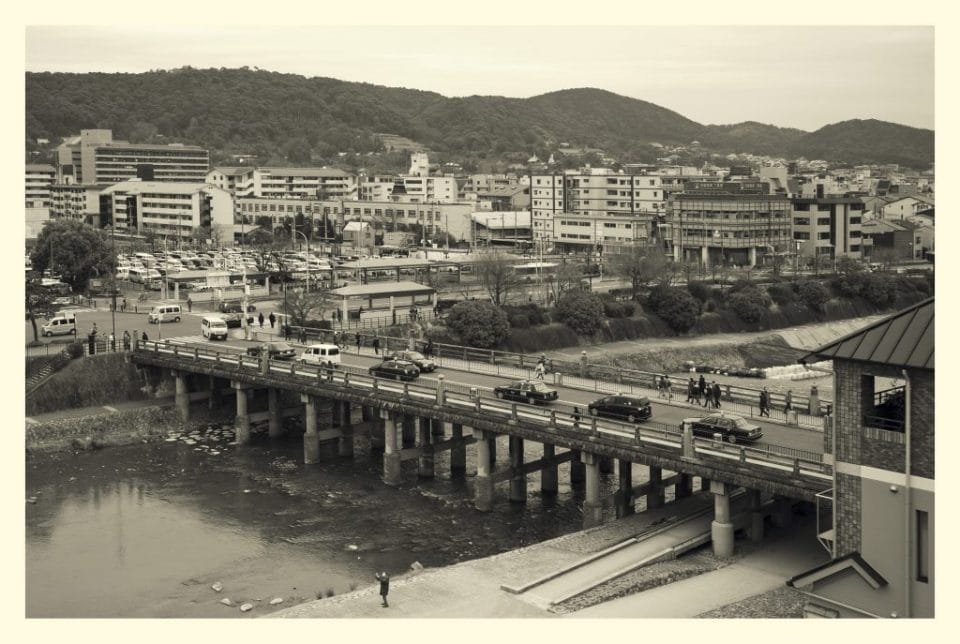

Sanjō Bridge. Courtesy of Russel Wong.

While discussing with Russel Wong on this project, I wanted to know more about his personal journey and understand his mission in Kyoto. At the same time, I shared with him what I will be presenting through the ukiyo-e. We went through the woodblock prints together and one of the prints that caught his attention was Utagawa Hiroshige’s “Nihonbashi”, from the series “Fifty-Three stations of the Tōkaidō”.

Courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum

This series of prints marked the journey one would take between Edo (today’s Tokyo) and Kyoto. Each print (although titled as “Fifty-Three stations of the Tōkaidō”, there are 55 prints in this series, including the first and last stop – Edo and Kyoto) depicts a post station to mark one’s itinerary.

My perfect benzodiazepine from late 2020 to present. Coincidentally, as the title of this guqin tune suggests — the Dream of Zhuangzi – was also a central nugget for Ukiyo, the Floating World. It was an old story about Zhuangzi, a Chinese philosopher of about the 4th century BCE, who fell asleep and dreamed he was a butterfly; on waking, he could not be sure he might not now be a butterfly, asleep and dreaming it was a man. We all have waking and dreaming, but how do we know which is which? Is one definitely more certain than the other? The conundrum is ontological. During the Edo period, this subject was often featured in paintings and prints.

Despite some variations in sights and scenes on the various post stations in later editions, Hiroshige always starts with Nihonbashi in Edo and ends with the Sanjo Bridge in Kyoto. Russel told me that he is familiar with this series and is very much inspired by woodblock prints while shooting in Kyoto.

He showed me his photograph of the Sanjo Bridge at the location where he imagined Hiroshige would have gotten his inspiration to produce his prints. I immediately felt that that was the link. The two bridges along the Tōkaidō route through a Edo-period woodblock print and a contemporary photograph that allow us to travel across time and space.

J.S.Bach’s Mass in B Minor or any of Bach’s harpsichord concertos – always work for me when I am organising my thoughts and particularly helpful during the preparation phase for my exhibitions.

Akafuku is a famous traditional sweet made and sold in Ise.

During the lockdown phase last year, I was out-stationed in Japan for a period of time. It enabled me to have a series of discussions with the co-organisers — Kobe Shimbun — who had kindly facilitated work meetings to discuss how we could present the woodblock prints to our Singapore audience. The initial idea was to present ukiyo-e through 5 Master Artists – Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Kuniyoshi. It was a fabulous idea however, I felt that we could attempt another perspective to challenge the conventional way to present ukiyo-e to our Singaporean audience.

Nihonbashi: Morning scene by Utagawa Hiroshige. Courtesy of Nakau Collection.

There are many genres that ukiyo-e covers such as travel, beauty care, pets and delightful animals, soul food/gastronomy, gardening mania and seasonal festivals. Many of these themes are still very relevant to Japanese people today. These are also the same things that perhaps attracted most Singaporeans and other international visitors to Japan. I felt that if we could arrange the narrative of “Life in Edo | Russel Wong in Kyoto” according to these themes, we could also make “Life in Edo | Russel Wong in Kyoto” a little more relatable to everyone. Kobe Shimbun and the lender, Mr Nakau Ei, immediately supported this idea. The rest is history.

—

“Enjoying the Doll festival” by Utagawa Kunisada, aka Toyokuni III. Courtesy of Nakau Collection.

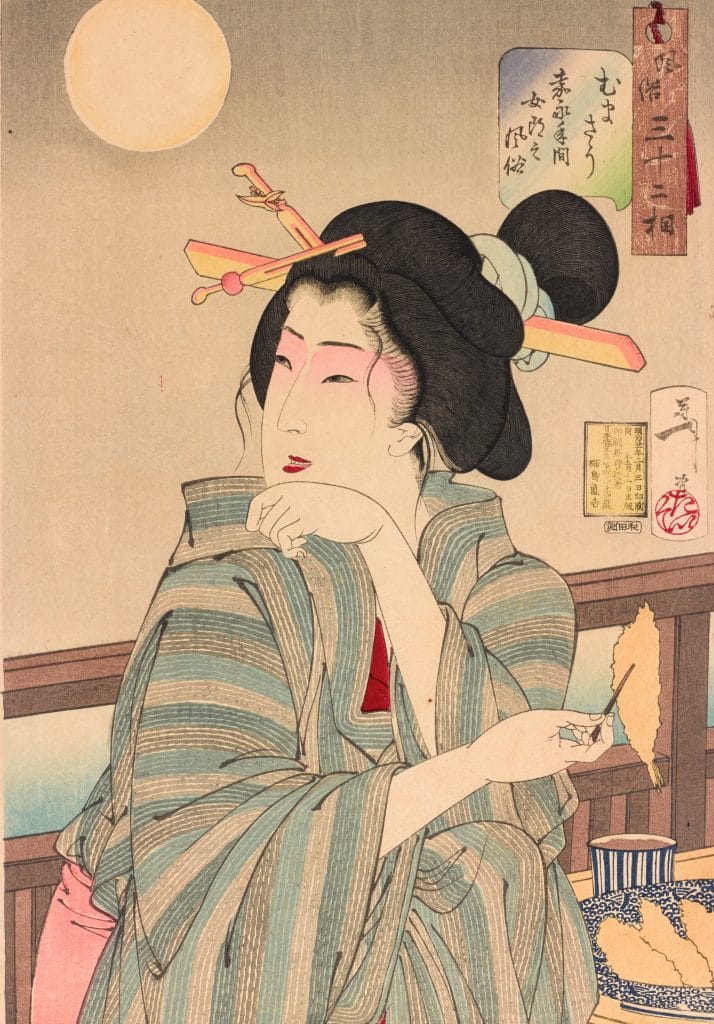

Ukiyo-e are fun, entertaining, and extremely informative to look at! Ukiyo-e contains valuable sources of information regarding lifestyles and cultural trends in Edo-period Japan.

In the most literal sense, ukiyo means “transient world” or “floating world”, and has the spirit of “going with the flow of the current, modern style”. Scholars of the time defined it as a realm of the imagination, where the passing moment and temporal flux were cherished for their own sake. Thus, the pleasure quarters and theatre district of Edo (today’s Tokyo), Kyoto, and Osaka captivated the popular imagination. A genre of Japanese prints and paintings known as ukiyo-e (e means picture) was born to capture these fleeting moments. In short, these pictures captured ordinary people (townspeople) engaged in leisure pursuits and day-to-day activities.

Looks delicious: Appearance of a courtesan in the Kaei period by Tsukioka Toshitoshi.

Today, ukiyo-e prints show us what interested the people of the Edo period, and they have also shaped how we view Japan. In a world without smartphone, television and the internet, Edo people consumed ukiyo-e much like how we are on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and other social media platforms.

Catch ” Life in Edo | Russel Wong in Kyoto” at the Asian Civilisations Museum from today till the 19 September 2021 or, click here to catch up with our April 2021 issue.