What is Hallyu, and why is it challenging the global currents of culture today? How does this wide-reaching wave rewrite the rules of fashion? In this deep dive, we uncover the complex relationship South Korea has with this international phenomenon and where everyone else stands in this conversation.

When a prestigious art institute like London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) puts up an exhibit dedicated to the rise of South Korean pop culture, it is crystal clear that this “K-wave” is no fad nor a regional phenomenon. Titled “Hallyu! The Korean Wave”, the exhibit amasses an impressive collation of South Korean drama, film, music, beauty and fashion that have found popularity in regions near and far from its place of creation, all to evince the cultural powerhouse’s profound and widespread influence on the world — and there are no signs of this force loosening its grip just yet.

V&A has always had a special relationship with South Korea as compared to its peers — it was the first British institution to publish a book about Korean art in 1918; it inaugurated the European tour of the National Art Treasure of Korea exhibition in 1916, and the institution houses the first permanent gallery devoted to Korean art in London. With this in mind, the significance of such an exhibition (“Hallyu! The Korean Wave”) multiplies tenfold. In other words, Hallyu has now acquired the decadent respect one might also give to South Korean traditional art, for its challenge of global currents of pop culture is nothing short of a marvel to behold.

It is not news. In fact, it has been happening for the past two decades, the “K” label slowly dominating cultural conversations in music, film, beauty and most recently, fashion or luxury fashion, to be specific — a landscape traditionally guarded and Eurocentric in activity.

“Widely recognised as fashion trendsetters, K-pop idols have become ambassadors for fashion and luxury brands both inside and outside of South Korea,” says Dr Rosalie Kim, V&A curator and lead creator of “Hallyu! The Korean Wave”. “They often enjoy a global MZ* audience that these companies can tap into, thereby rejuvenating and/or culturally diversifying their image.”

“Widely recognised as fashion trendsetters, K-pop idols have become ambassadors for fashion and luxury brands both inside and outside of South Korea,” says Dr Rosalie Kim, V&A curator and lead creator of “Hallyu! The Korean Wave”. “They often enjoy a global MZ* audience that these companies can tap into, thereby rejuvenating and/or culturally diversifying their image.”

From G-Dragon and Blackpink’s Jennie at Chanel, Kai and IU at Gucci to more conservative and anti-trend Houses like Dior, Balenciaga and Bottega Veneta following suit, K-pop idols and celebrities are fast becoming a staple presence in seasonal campaigns and shows, and for one and one reason only — the attention of their fans.

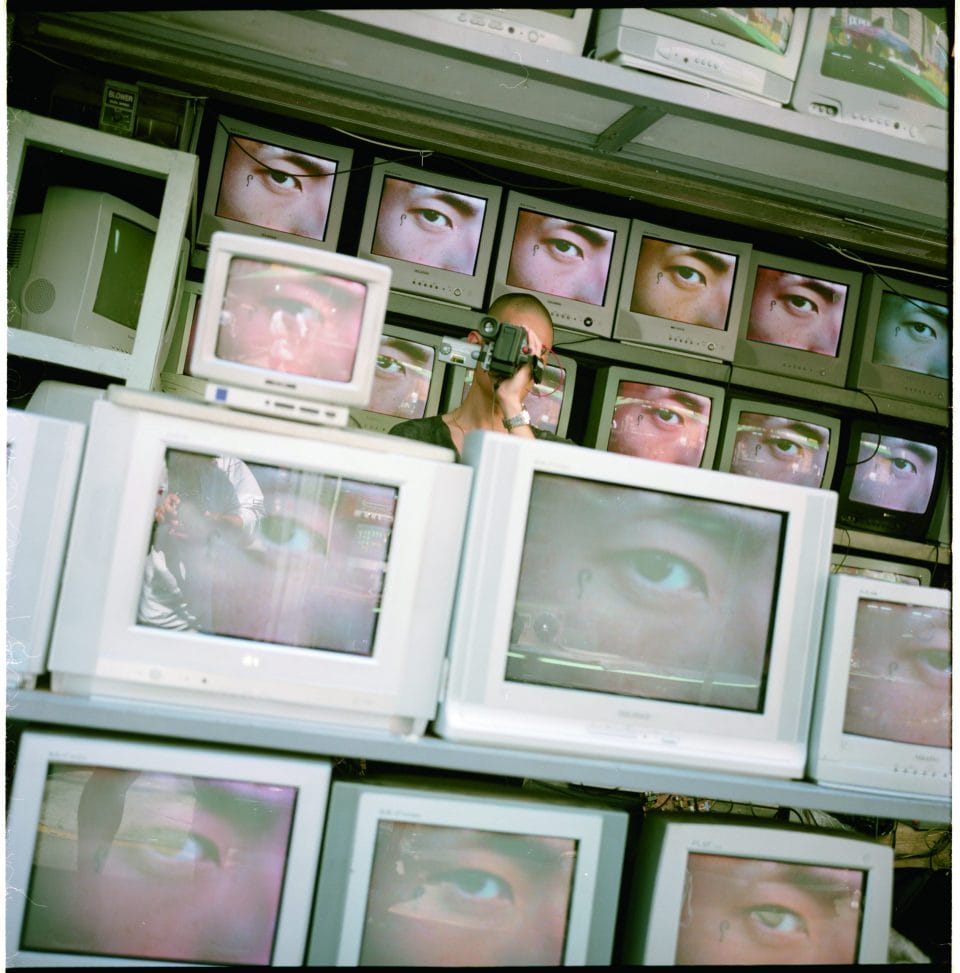

K-pop fandoms, the other important half of this multimillion-dollar industry, is big, dynamic and powerful because of its unique demographic — affluent, tech-savvy, young and impressionable. Thanks to the speed and borderless reach of the Internet, these fandoms overcome geographical and language barriers to form strong-knitted communities that interact with the generosity of its “gift economy” — a complex system of giving, receiving and reciprocating — and impossible loyalty, thus becoming an irresistible market of opportunity for luxury brands.

Understanding why these fans are changing global cultural currents requires a deep dive into South Korea’s social fabric, acknowledging first the active role South Korea’s traumatic history continues to play in structuring this global cultural force and contemporary South Korean society — the true first generation of K-pop fans.

As a people, South Koreans are industrious, passionate, adaptable and have a huge appetite for learning — traits that arise from the widespread practice of Confucianism and Shamanism. But emerging from the Japanese occupation and the Korean War as one of the world’s poorest countries in the 1960s also made South Koreans hyper-competitive — a key reason why the country could move from third to first world in 30 years.

As a people, South Koreans are industrious, passionate, adaptable and have a huge appetite for learning — traits that arise from the widespread practice of Confucianism and Shamanism. But emerging from the Japanese occupation and the Korean War as one of the world’s poorest countries in the 1960s also made South Koreans hyper-competitive — a key reason why the country could move from third to first world in 30 years.

Fiona Bae, author of Make Break Remix: The Rise of K-Style — an extensive compilation of interviews with South Korean creative trailblazers — writes that being a small country that was reliant on stronger countries exacerbated South Korea’s insecurity and longing for external recognition, creating a modern society that was and still is materialistic, status-driven and primarily dominated by a herd mentality or “copy-cat” culture.

While this culture is derived from the practice of copying Japanese and Western products to support and boost exports, it also stems from the fear of standing out in the face of economic and political turmoil. As a result, haircuts and clothes worn were kept standard and practical, and the re-creation of goods was purely aesthetic. The rush to compare with what was deemed “successful” or “popular” in fashion even turned the manufacturing sector into a sustainable fashion ecosystem that allows budding designers to flourish and develop their work — yet another reason for the competition to manifest and even thrive.

“If a South Korean celebrity sports a certain dress in a K-drama, factories are able to copy and produce it by the following day. That’s the speed or efficiency making clothes there affords — with quality materials at an affordable price,” says Bae.

“If a South Korean celebrity sports a certain dress in a K-drama, factories are able to copy and produce it by the following day. That’s the speed or efficiency making clothes there affords — with quality materials at an affordable price,” says Bae.

And that efficiency extends into the structure of the K-pop industry itself; its cookie-cutter training systems for idols-to-be; formulaic marketing strategies to position and package these groups; K-pop music and its accompanying wardrobe being an interpretation of the popular Western counterparts in particular.

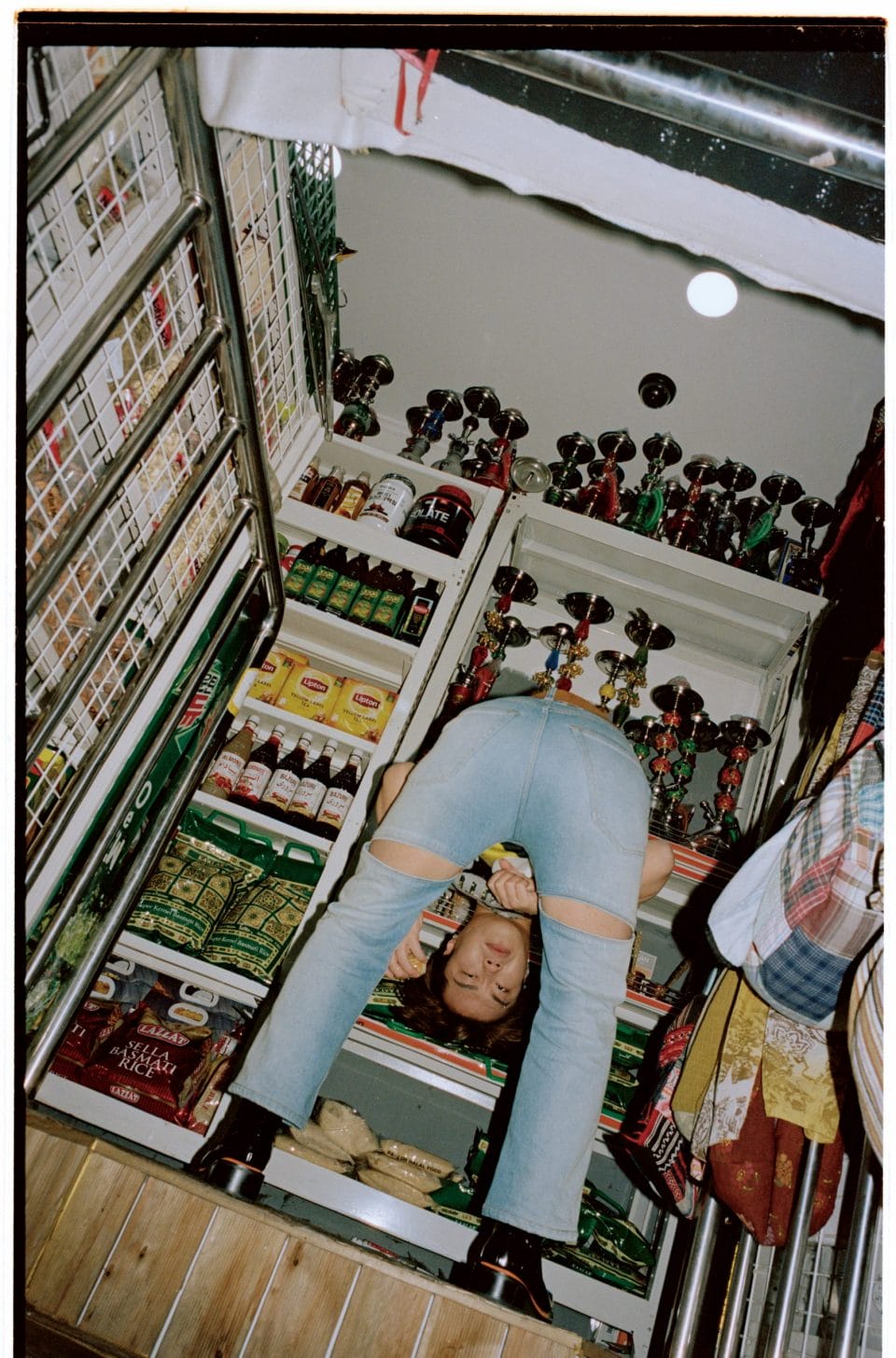

Bae says that today’s South Korean fashion landscape is still largely divided by prominent genres or communities that, while more in number and diverse in type, are still almost strictly homogenous. “Trends move so quickly in South Korea that it’s hard for the older generation to follow, so the young South Koreans find it hard to sympathise or respect what their parents are wearing,” says Bae. “This strong disconnect between generations in South Korea from rapid socio-economic development means you cannot easily talk to your parents about what you enjoy in fashion, so you end up building a stronger bond with your peers.”

When an entire nation becomes hyper-competitive out of survival, everyone living there is also forced to experience the oppression of nationalistic propaganda and its fatigue. “Because South Korea is so competitive and repressive, there is so little opportunity even if you follow these narrowly defined paths of success. There are not enough jobs offered at the end of the day, so figuring things out on their own has become less of a rebellion than an act of desperation.”

Facing a heady mix of influence from Japan, China, and the US emphasised the urgency of South Koreans’ search for identity. It resulted in what Bae notices as a redefinition of “authenticity” — an embrace of the copied and the original. While this can largely be attributed to the adoption of Western values of individualism, originality and freedom of expression, this bold “mix-and-match” spirit is undeniably reminiscent of the South Korean’s disposition towards resourcefulness and earnest ambition, which has now become the unique selling point of K-pop as a cultural product.

Facing a heady mix of influence from Japan, China, and the US emphasised the urgency of South Koreans’ search for identity. It resulted in what Bae notices as a redefinition of “authenticity” — an embrace of the copied and the original. While this can largely be attributed to the adoption of Western values of individualism, originality and freedom of expression, this bold “mix-and-match” spirit is undeniably reminiscent of the South Korean’s disposition towards resourcefulness and earnest ambition, which has now become the unique selling point of K-pop as a cultural product.

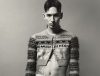

“K-pop idols used to have a single dimension approach to wardrobe, either going cute or sexy. Even wearing school uniform was popular. Now look at Blackpink — their style is way beyond that. They pull out such sophisticated and interesting fashion choices because the talented stylists these girls work with don’t just look to luxury for clothes. They incorporate pieces from street or cult brands with one aim in mind: to make the girls look impeccably good and natural, wearing things that seamlessly fit or bring out their physicality and character,” says Bae.

In a conversation with Kim Youngjin, a stylist to K-pop artistes like NCT, she said that it used to be nearly impossible for him to get luxury brands to dress NCT. Now, the brands love them. “Luxury brands were used to elevate the status of groups, but now it’s a two-way street. It’s even become somewhat of a rite of passage or measurement of success for K-pop idols to get brand ambassadorships because being backed by widely respected brand names reflects the influential power these idols have, most commonly quantified by social media account following.”

And precisely because fans more readily accept influence from the direct and more private medium of social media, stylists and the artists themselves incorporate street or local brands to balance out.

Bae cites that fatigue from the repetition and overexposure to ambassadorships is changing the tides of K-pop dress again. “For K-pop idols to survive and maintain their credibility and popularity with fans, they have to ensure that they are more than a brand ambassador. So while there will be agreements and requirements for them to wear or carry the brand, they don’t need to rely on this one brand to be a style icon beyond official schedules,” she says.

Bae cites that fatigue from the repetition and overexposure to ambassadorships is changing the tides of K-pop dress again. “For K-pop idols to survive and maintain their credibility and popularity with fans, they have to ensure that they are more than a brand ambassador. So while there will be agreements and requirements for them to wear or carry the brand, they don’t need to rely on this one brand to be a style icon beyond official schedules,” she says.

This explains how even the traditional Korean dress, hanbok, is now looked to as a means of staying competitive.

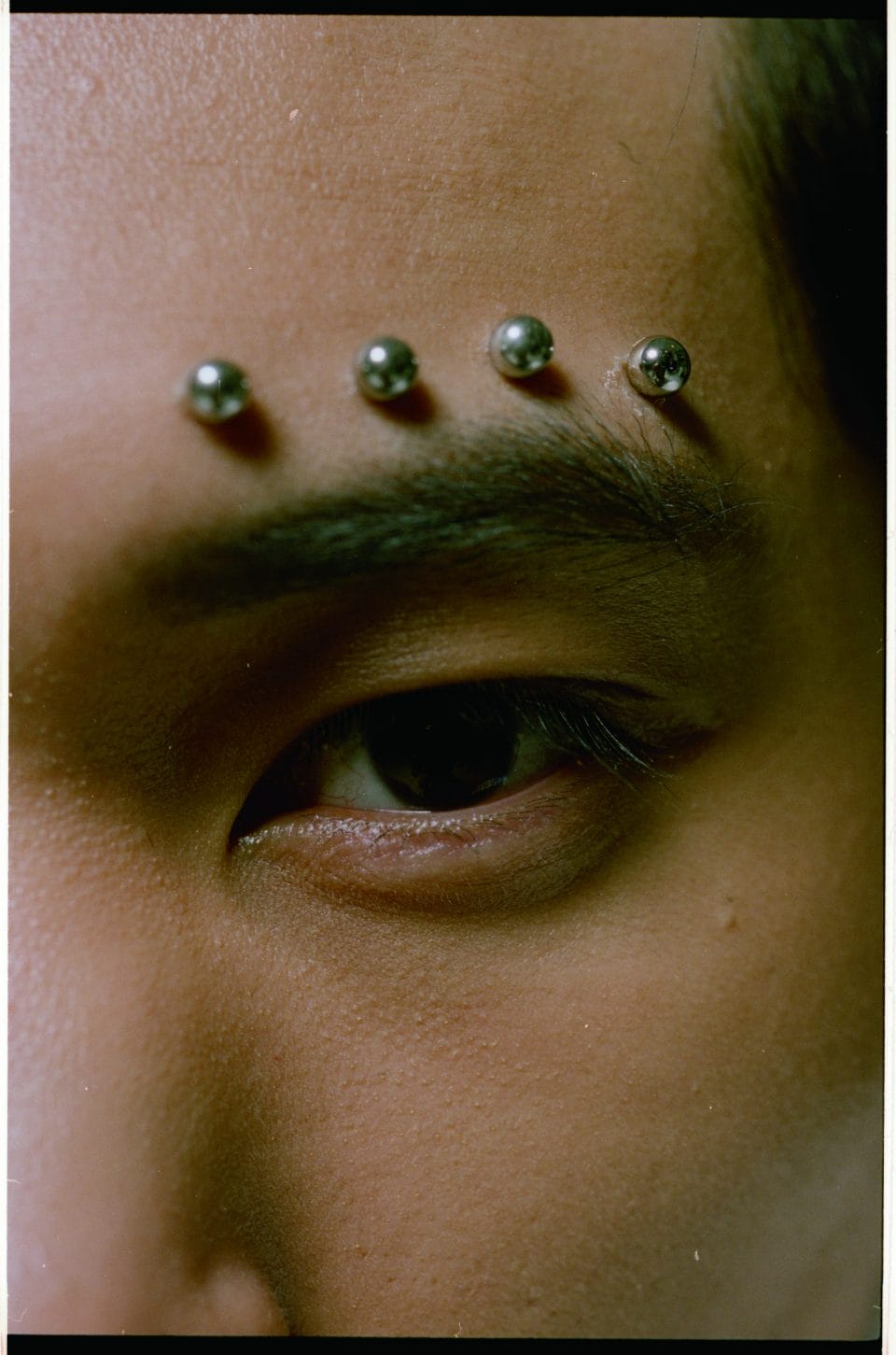

Dr Kim says the South Korean government has tried many times, but in vain, to bring back hanbok to daily life since the 1960s. “It is the concerted effort of hanbok designers, stylists, manhwa (a artists and fashion magazines from the mid-2000s onwards, amplified by the global success of K-drama and K-pop, that made hanbok what it is today and exploded at a scale never seen before through internet and social media platforms”.

“Hallyu provided an opportunity for many hanbok designers and stylists to take artistic license and liberties with historical accuracy to expand hanbok’s aesthetic appeal and wearability while underscoring its place of origin,” says Dr Kim. “Despite criticism bemoaning the loss of its authenticity and original beauty, these modern hanboks have kept their creative essence and gained momentum with the public, particularly the youth. It is both a fashion statement for young trendsetters and members of the South Korean diaspora affirming their cultural heritage, while for K-pop artists, the hanbok is enhancing their dynamic choreography whilst underlining their South Korean identity.”

The significance of having designers like Baek Oak Soo and Minju Kim — whose works are either designed as or inspired by the hanbok — represent Korean fashion in “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” show how the South Korean youth often readily adopt a hybrid approach to fashion, embracing hanbok alongside contemporary fashion, mixing styling, and reflecting a market between high-end luxury brands and high-street fashion.

The significance of having designers like Baek Oak Soo and Minju Kim — whose works are either designed as or inspired by the hanbok — represent Korean fashion in “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” show how the South Korean youth often readily adopt a hybrid approach to fashion, embracing hanbok alongside contemporary fashion, mixing styling, and reflecting a market between high-end luxury brands and high-street fashion.

Dr Kim says, “What is interesting is that many contemporary South Korean fashion designers include nods to their cultural roots in their design, be it in the choice of fabric, stitches, pattern making, or decorative motifs, despite their often-international biographical trajectory.”

It has even created a new diaspora of sorts since there are a lot of young South Korean designers who pursue fashion studies abroad before coming back. Bae says, “Being affluent enough to study fashion and design overseas is actually a very recent phenomenon because we had been poor for a long time.” This re-emphasises how tangible and real the effects of South Korea’s history are on the growth of the fashion scene there today.

So where does this lead us as consumers of global culture? Why is it important to acknowledge this specific surge of cultural momentum when numerous other cultural gears are turning with influence in the fashion industry? Dr Kim says, “South Korean pop culture has provided a global platform for some of those luxury brands to reach greater audiences, while those brands imbued Hallyu with a strong fashion sense, enhancing one another’s profile globally.”

So where does this lead us as consumers of global culture? Why is it important to acknowledge this specific surge of cultural momentum when numerous other cultural gears are turning with influence in the fashion industry? Dr Kim says, “South Korean pop culture has provided a global platform for some of those luxury brands to reach greater audiences, while those brands imbued Hallyu with a strong fashion sense, enhancing one another’s profile globally.”

This not only effectively means that the K-wave is a part of everyone’s lives, but it also proves that the transition from subculture to mainstream culture is becoming increasingly seamless and complex. Perhaps the stronghold South Korean pop culture has on luxury fashion requires a less factual and more nuanced understanding of a culture’s history. After all, the “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” exhibition and the decadent stage outfits of K-pop idols are just the surfaces of how deep contemporary South Korean culture’s influence has been rooted into our streams of consciousness — that’s for another deep dive we will embark on in due time.

*a term used only in South Korea that refers collectively to the Millenials (born 1981-1995) and Generation Z (born 1996-2005)

This story on the Hallyu phenomenon first appeared in our May 2023 issue. Click here to catch up with it.