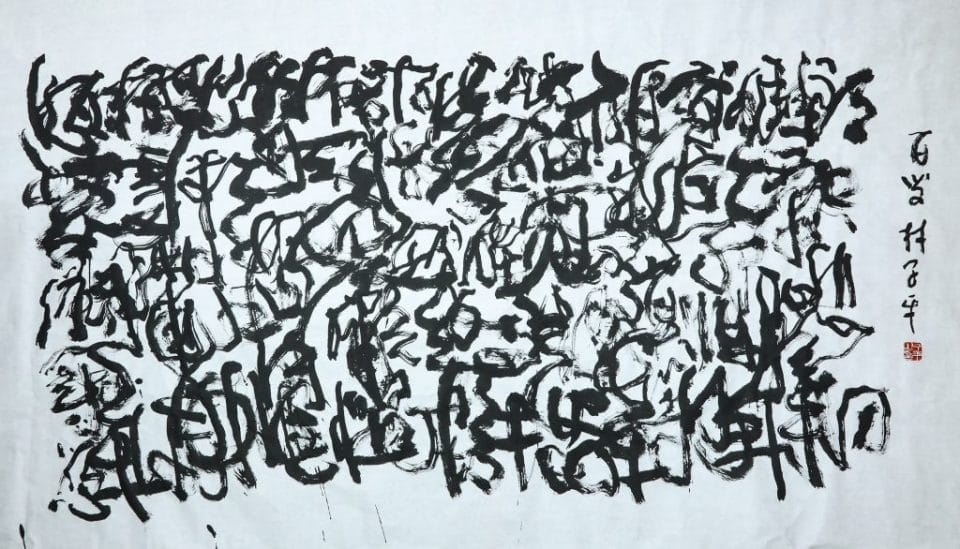

With all due respect to Lim Tze Peng himself, the centenarian is an OG of Chinese calligraphy (Lim also has the wonderful art of Chinese painting in his belt). Counting Lee Man Fong, Cheong Soo Pieng and Liu Kang (the pioneer generation of Nanyang Artists) as his mentors, Lim has been applying deft strokes to paper since the 1940s. No mean feat because after all, the art has such a prestige level. While the naysayers might not agree — Europeans think that the art of calligraphy ranks lower than painting due to the materials used — it can be assumed that Chinese calligraphy is fine art itself due to its strict codes of aesthetics.

Each Chinese written script consists of several thousand individual graphs and in each graph, is an invariable number of strokes that has to be precisely executed in a set order. However, the order is dependant on the artists’s own interpretation. Does he or she choose to swiftly or slowly make a stroke? Or does the artist want to emphasise a character with great force or delicate pressure?

All of these nuances — the flair and the forthrightness — has been documented in “Soul of Ink”, 10 works by Lim Tze Peng himself in the year he turned 100. Here, he takes us through the start.

—

“Soul of Ink” by Lim Tze Peng is on display at the Arts House Gallery from today till 30th June.

How did you get started with calligraphy?

I had an interest in calligraphy at a very young age. Even as a boy, I would score distinctions in primary school. The teachers saw I had a firm grip on the strokes of Chinese calligraphy and encouraged me. Those early years laid the foundation for me. Today, the strength of my strokes are the base of all my art, even abstract art.

—

Abstract Calligraphy by Lim Tze Peng

What do you think calligraphy perhaps does for one’s attitude or temper — or even the ego?

No two calligraphic works are alike, even by the same calligrapher. For me, I need a good night’s sleep to execute strokes that are not just firm, but creative. I am already 100 years old, but I still practise every day. When I stop writing calligraphy, my hands get rigid and the strokes cease to flow naturally. It is a discipline that humbles you, it is an art form that reminds you that perfection is elusive. As a calligrapher, I am a slave to the discipline, not a master. I am rarely totally happy with what I write. Calligraphy keeps me humble.

—

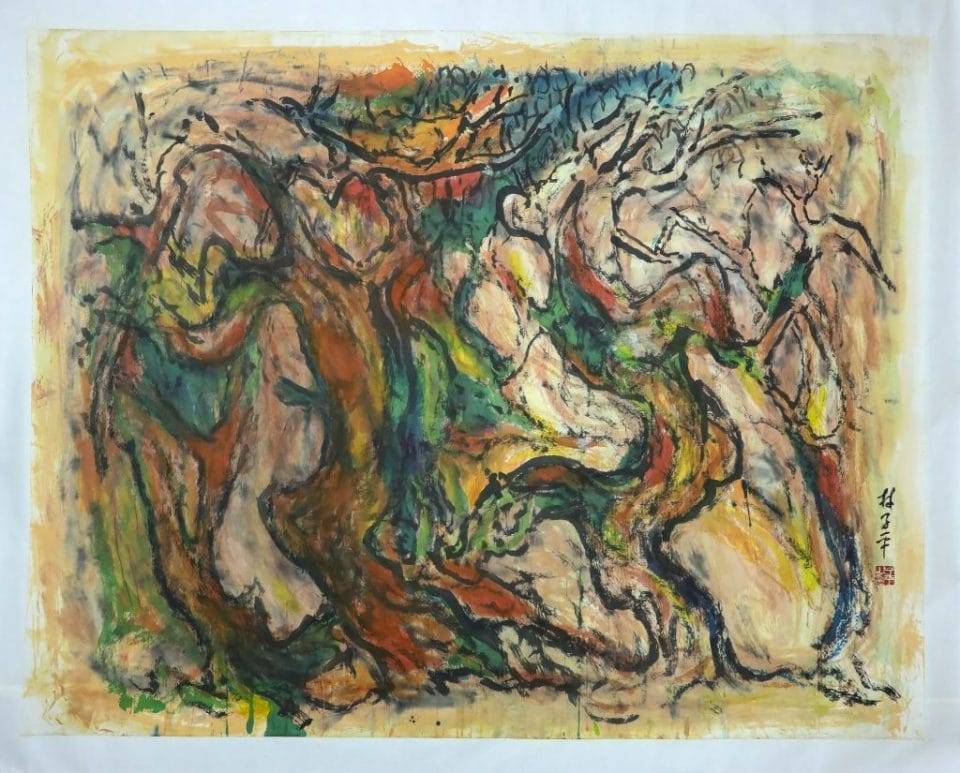

Tanjong Rhu Riverside by Lim Tze Peng.

How did you curate the works for “Soul of Ink”? Was it difficult for you to omit some of your works?

“Soul of Ink” is not just about my art. It is as much about me as the artist, the man behind the art. The author Woon Tai Ho observed me, talked to me and my family, collectors and friends. He has written about the motivation behind my art and the passion that drives them. With the help of some experts, we chose 10 works that I have executed and completed in this year that I am 100 years old.

Even with such a sharp focus I had difficulty choosing 10 representative works, but I did. The critique of the 10 works is in the last chapter of the book. It sums up well what I have been doing since I reached 100.

—

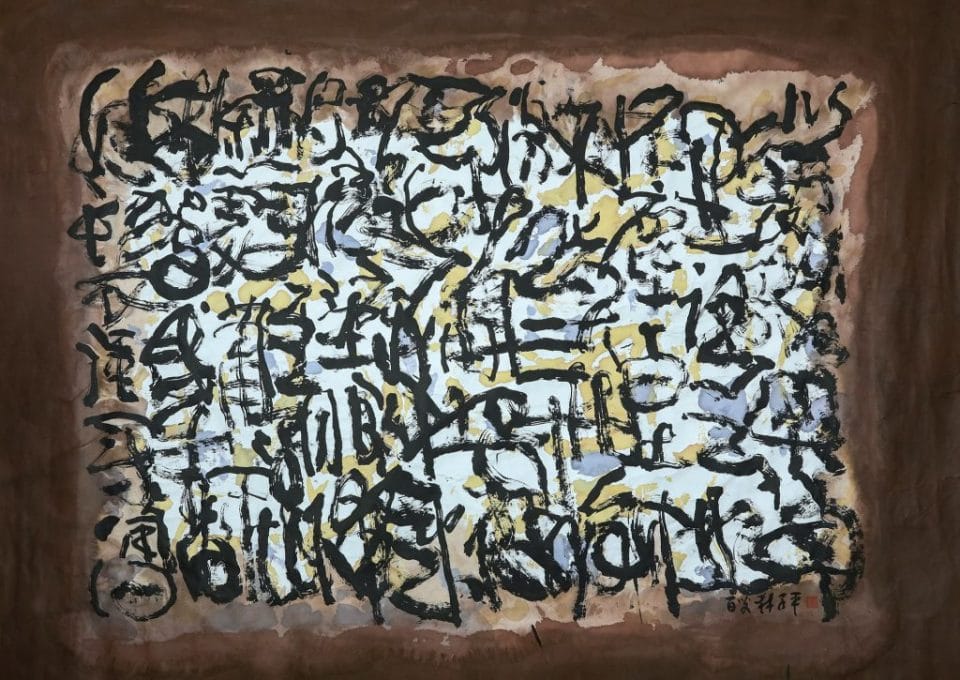

Abstract Calligraphy by Lim Tze Peng.

Can you talk about two or three of your favourite works in “Soul of Ink” and why you chose them?

I have no favourite works, every single piece of art created is a child of mine. No good parent will tell you which child he likes over another. Every child is special, every child is precious. To answer this question in another way, in the early days a collector really liked two of my representative works on Chinatown and Singapore River. It took me a long time to agree to sell him the two works. When he persisted, I eventually relented. When the paintings left the house, I could not sleep for a long time.

—

Kelongs Of the Past by Lim Tze Peng.

In the many years you’ve been painting, what do you think has been the biggest shift in culture or even the way people paint now?

I believe in paying my dues, I believe I have come a long way because it is the only way to grow and learn with the requisite experience. Before Picasso came up with cubism, he was a figurative and naturalistic painter. So was Piet Mondrian, before his architectural abstracts, he was a naturalistic painter of trees and landscapes. There is a process where an artist finds his language and voice, his form of expression and eventual destination, what he or she is eventually known for.

Today, quite a young few artists are abstract artists overnight, or feel they have established a signature style very early in life. I wish to tell them, don’t rush.

—

Tree Series by Lim Tze Peng.

Why did you then decide to incorporate more colours as of late?

I allow myself to change. As I grow older, I feel freer and more relaxed. During my early years, I painted on location. Then, I had limited time at any one place, I needed to capture the scene before the light changed.

When I reached 80, I only painted in my home studio, relying only on my mind as a resource. I am a lot more inventive and free. In the book, there is a chapter on Rainbow after dusk — it describes me well.

—

Abstract Calligraphy by Lim Tze Peng.

Do you listen to music while you paint? Are you able to let us know four to five tracks if you do?

I listen to music a lot, but I listen to music while I am resting. My mind is like a sponge, it absorbs everything I hear. When I paint, I replay them in my mind.

I listen to a wide range of music, from opera to folk. Some Hokkien folk songs bring tears to my eyes.

“Soul Of Ink: Lim Tze Peng at 100” is on display at the Arts House Gallery from today till 30 June 2021. Click here to catch up with our June/July 2021 issue.