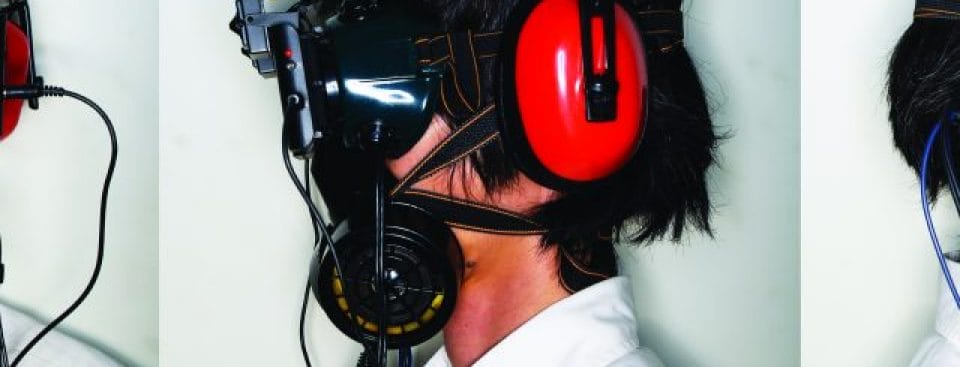

Pictured Above: ‘Performing The Smart Nation’ by Teow Yue Han

Globally, the continuous threat of COVID-19 is wearing thin on conventional and pragmatic perspectives of art-making and presentation. What was once a pre-formulated system of creation, investigation, presentation and sale has been widely reconsidered by artists and curators alike.

Just in March this year, New York’s Armory Show opened on schedule despite concerns of public health safety and low attendance; performing well with huge sales and a high visitation. As it was happening, the world observed a global lockdown. Galleries had their doors locked and mass cancellations of fairs scheduled to take place this year have been cancelled.

With the inability to practice beyond the confines of a studio or gallery, industry change-makers are looking beyond the tangible for answers — sparking a return of interest towards the digital. The result is the rise of the virtual gallery. For larger organisations, this includes putting out decades of archives digitally, where one may opt for a guided tour over Zoom or a series of panel discussions over an Instagram live stream.

Independent artists — with fewer resources and limited access to relief — have utilise open-world virtual games, such as IMVU and Minecraft to create a never-before-seen digital landscape of art.

Life Circuit by Urich Lau

However, art is defined by control — of one’s senses and perception. The composure for artists who delved over the environments to construe the experience is now limited to common devices. This poses a huge limitation for artist who delved in traditional mediums. It is hard to imagine famed installation artist, Chiharu Shiota’s work without the in-person experience of its grand scale and detail, let alone from a six-inch screen.

Although virtual reality appears to be the solution, it is still largely inaccessible.

It raises another thought, how would a shift towards the digital affect the complicated perspective of art value as well? After all, the art industry is lawed with the simple rhetoric of supply and demand. With no predetermined course of action and detailed studies towards a large scale digital migration, it becomes a tricky situation.

A better understanding requires an examination of the use of technology, a process that parallels a medium that has become trendy ever since the global lockdowns occurred — digital art.

Digital art is a practise of new media that involves the use of technology to create visual works. It was first conceived as computers became more accessible in the 1980s, giving artists autonomy to render objects, forms and spaces that were once inconceivable. With the help of the internet, the medium became a sought after thought process for the relationship between technology and media.

Yet by the standards of the day, the value of a digitally rendered work that is easily reproducible is lagging behind its traditional counterpart — because the issue with art value and digital paintings stems from the idea of an original.

In most cases of digital art, there can be infinite copies of the original with no guarantee of a controlled supply of prints and editions. This inflates the supply levels beyond the control of the artist. Unfortunately, it devalues the work as it is simply too accessible. If applied to the current status quo, the result is largely a continuous sale and presentation of traditional art in the same elitist fashion.

The question that remains is — how better can we appreciate works of art online and what can we learn from this?

To better understand this, four artists share their reflections on digital art in the time of COVID-19 and their thoughts on the medium in Singapore.

__

Urich Lau — Artist, Educator & Co-founder of INTER-MISSION

Talk us through the nature of your work and how it has developed from your time as a student to your time as a lecturer. Was digital art your calling, and were other narratives considered?

I started my art education at the then Lasalle- SIA College of the Arts in 1994. I studied Fine Art, which also consisted of art history and theory. And I have always been into my reading of subjects in science, technology, philosophy, and psychology. At that time, there were no classes on digital or media art, not even video-making.

The most “technological” training I had was photography using the SLR camera and darkroom techniques. As I pursued my BFA and MFA in the University of Tasmania and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, I extended my practice into video art and digital art.

My main interest is still photography, and that led to stop-motion and video-making.

When I bought my first computer — the Apple Powerbook G4 — and experimented with more camera work is when I progressed into digital art. At the same time, I started to present work in exhibitions and projects. One obscure opportunity led me to co-curating a video art exchange exhibition in Singapore and Bandung in 2006, even when there were no interests or focus for video art or media art in the Singapore art scene.

And from there, I just continued until now.

__

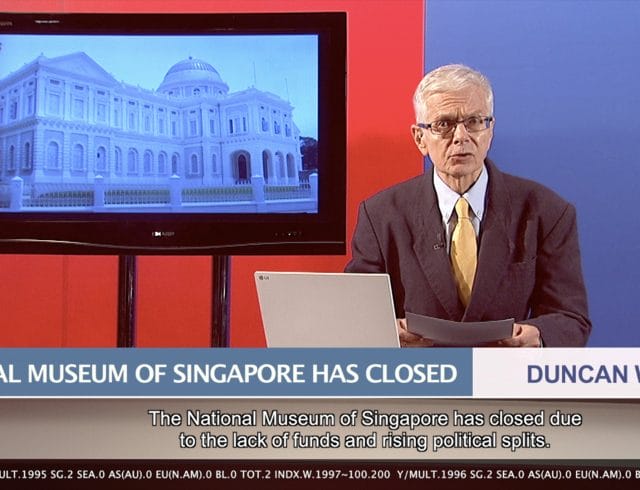

THE END OF ART REPORT

On your collective’s website, it states that “INTER—MISSION builds transnational networks to promote sustained dialogue and engagement with media practices”, was this something you found lacking in Singapore? What were the motives that drove you to create such a profound agency for digital art?

Yes, our focus is on interdisciplinary practices and discourses in technology, media and art. We also believe that the collaboration with artists and curators from other countries on kindred issues and subjects in art and technology is essential for the exchanges of ideas and critiques. T

here is a lot of art in Singapore but not many avenues and platforms for dedicated practices in digital art, which requires rigour in research and discourses.

I find that contemporary art in Singapore still revolves around the conventional or traditional methodologies and techniques. Although the fundamental knowledge and skills are important, the condition remains stagnant there. There is a lot of growth in funding and support over the last 20 years or so, but it is not growing the field of art technology.

Sometimes I would hear comments about digital art being likened to be cold, convenient or lacking the “human touch”, but I don’t see how that emphasis in technology would undermine the integrity of art, skills or techniques.

Technology as an art medium is just a medium, the important part of art practice is still about the concept and the understanding of contexts. We also cannot avoid talking about world trends and evolutions either. At the beginning of the 20th century, art was a critique of the traditions and the establishment; in the mid 20th century, art redefined that critique; in the late 20th century, art digitised and decoded that critique.

What is the role and position of Singapore contemporary art now, in the world stage that is using and showing, technology and media art as the language that bridges transnational dialogues and exchanges? It is also ironic when Singapore has the capability in education and sustainability in developing technology in the arts. We cannot just emphasise on production and regurgitation of shows but lack the efficacy for research and cultivation for technology in art.

There are many examples of festivals and events that showcase spectacular works using technology and digital media, but not all art in technology is art — some are just technology.

__

Life Circuit

The exploration of technology and media is constant throughout your works, where do you derive your observations and perspectives from?

I mentioned about my art training in various subjects in fine art, with my interests in science, technology, psychology, and philosophy, I am also a nerd in world history and politics. I also like reading up on the epistemological development of machines, computers, the internet and the likes. These topics are in tangent with human civilisation and development of societies.

For instance, the democratisation of the camera, imaging and video formats gave rise to the independent documentary or filmmaker.

We are (almost) free to walk around and capture images from life to form our commentary or critique. Although I work with media art, my influences initially come from photography and film. I am interested in the mechanics of moving and still images, and the capacity to convey content and metaphors.

I like documentary films and photographic works. The camera, video, and photography are tools but they are also the artist’s media.

Sometimes when asked with a similar question, I would joke that photography is my first love.

__

Life Circuit

Do you think the use of technology in art is just a trend and that its appreciation will quickly disappear once the attention of the art world moves towards a different trend?

If the world or Singapore sees technology in art as just a trend, then I would say we have regressed in creativity and innovation. Recently, I was reading back about Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) by Robert Whitman — who was one of the key figures in the movement — who is a performance artist and also worked in theatre.

His work was highly innovative and he often collaborated with engineers and scientists in the 1960s and 1970s with the uses of technology and telecommunication projects. Some of the projects that he worked on had created some impact on developing countries, and had contributed and propelled the use of the “video conference”.

I think the romantic idea of being an artist is detrimental to creativity. The artist’s practice should also involve constant research and experimentation. Interdisciplinary and collaborative work is indispensable as well. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde’s “the artist as philosopher”, it may be reasonable in the antiquated era — it is more relevant for the artist today to also be a scientist, technologist, environmentalist, stoic and futurist.

Technology is a tool and a medium — but above all — it is also an art form in the contemporary and future context.

__

AI-generated artworks have become increasingly popular and fall within the same spectrum of digital art. On account of evaluating the purpose, soul and humanity of the work, do you believe that AI-generated art is human at all, and should they be valued the same as art made by humans?

Yes, the art collective OBVIOUS had been in the news for its AI that created paintings and was sold at high prices. The value of art is not just about the paintings or technique used, but it is the transgressive and novel idea that creativity is not exclusively human quality.

One of my interests is reading but also reading up on influential titles and authors.

For example, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, which is regarded as the first work of science fiction. Frankenstein’s monster is a crude imitation of a human, yet it reveals the inefficacy and flaws of humanity while it is learning how to interact, communicate and obey its maker. The monster is the “critique of reason” for post-humanistic nuances — the more we use AI or technology, the more we understand ourselves.

Engaging technology in the art will not devalue or undermine art-making, rather it will reform the intent and motivation on why we still make art today.

__

Teow Yue Han — Artist, Educator & C0-founder of INTER-MISSION

If you had to describe your works to someone with little to no knowledge of art, how would you do so?

My work questions our visible and invisible interactions with technology, often through live performances, involving myself or movement collaborators. It often happens within a constructed environment that imitates structures we encounter in the Smart City, with materials ranging from a selfie stick to a text-to-speech voice.

Audiences are invited to be co-creators of the work through their participation, allowing the work to develop further.

__

We explore the values of digital art and how COVID-19 has forced artists to migrate online in this issue. However, to label you as a digital artist would be a huge injustice, considering the different levels of media and mediums found in your portfolio — how would you describe the nature of your work then?

I guess the category of digital art refers to art that utilises digital media, and is mostly accessed online and viewed through a screen. It’s also interesting how the Latin word for digital — “digitus” — refers to the finger or toe as a unit for measurement, pointing to the body as an origin of the digital.

Digital information is created as we swipe our smart devices, type on our keyboards, or when we walk past CCTVs and sensors.

My work stems from the physical body, how it interfaces with the digital realm, and the resulting feedback loop that occurs, where the digital mediates our relationships with one another. For example, live dance performances can take place between a museum in Singapore and a studio in London through a video call. In this case, the physical movements of the dancers and audiences in both cities are created in response to the real-time digitised movements seen through visualisations.

The nature of my work can be described as intermingling physical and digital gestures.

__

Heartware

The exploration of interaction with technology is constant throughout your recent works, where do you derive your observations from?

My work stems from my curiosity in what I call digital movement, thinking about how the movement looks like when it is digitised, or entangled with a digital layer. For example, in Pokémon Go, movement becomes currency. We hatch an egg when we move, explore new Pokéstops when we physically reach a location, cafes purchase lure modules to lure not just Pokémons but its customers.

The game radically transformed the movement of the public through digital augmentation. At the same time, because this movement is digital, it can be hacked as well. Players teleport to Paris to catch Mewtwo, by altering their geolocation, or in the case of Singapore’s National Steps Challenge Fitbit — trick the accelerometer to think that they are walking.

This curiosity leads me to research about larger political structures that govern and orchestrate movement and how we experience it, individually or collectively. More importantly, how we can find new modes of connectedness beyond what is prescribed.

Recent interests include undersea internet cables running through Singapore, Smart Nation Initiatives such as Virtual Singapore (Singapore’s equivalent of Google Earth), Tiktok and machine learning, the death of bike-sharing due to geofencing, and of course the recent pandemic and social distancing measures.

__

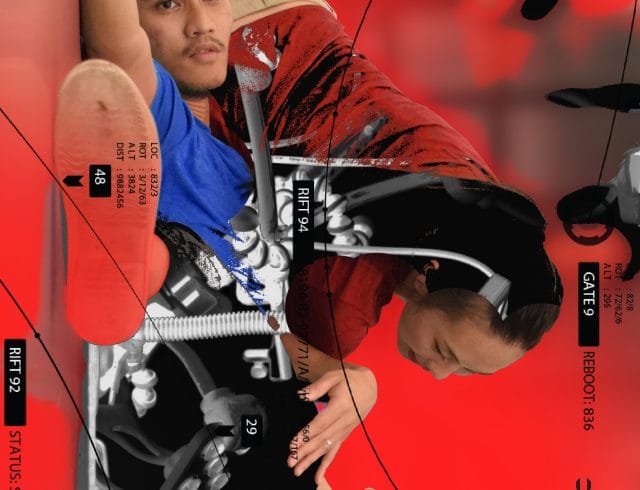

Alice, Bob & Eve

Performance is a medium you’ve often used to express the psychology of your works, and it is an inherently human element that is juxtaposed with technology, machines, and the digital — is the combination of both elements essential to the way you work?

Dancers now conduct their rehearsals on Zoom, collaborating through video calls, turning the physical spaces of their homes into a digitised dance studio. This is reminiscent of synchronous telematic dance performances such as Johannes Birringer’s project ADaPT (Association of Dance and Performance Telematics, 2001), or Company in Space’s Incarnate (2001), both using live-feeds to enable collaborative performance to take place over different countries, spaces and timezones.

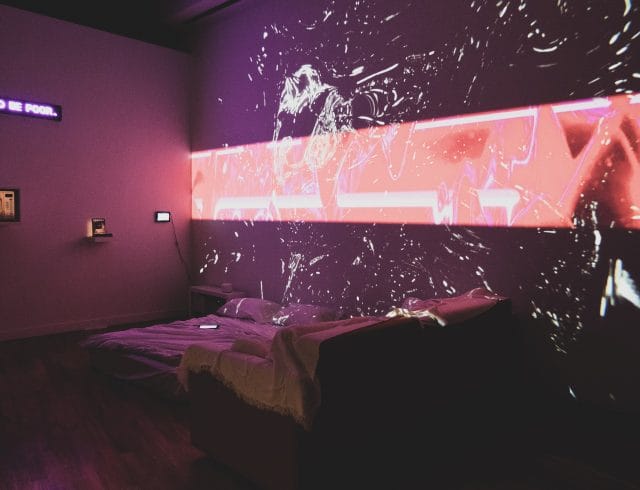

My series Performing the Smart Nation thinks about how our daily gestures become data flows that create the Smart Nation in real-time, which considering ideas such as live presence and mediated bodies, physical and digital spaces, and the camera’s relationship to the body; all of which are experiences that we have in the present moment as we conduct our social gatherings online.

With the pandemic, the ability for the government to curb the flow of bodies becomes even more critical, with Apps like Trace Together for contact tracing. When we build with technology, it tends to focus on scientific and practical knowledge, which is often reductionist and functionalist, leaving out wider nuances.

Performance allows us to envision and enact a collective future that allows for other forms of knowing, such as knowledge derived from practice, deliberation, and experience.

My performance Alice, Bob & Eve (pictured above) took the form of movement research living laboratory, where the movement was used to facilitate interactions within the laboratory and in turn opening up questions about how we can understand and transform these existing patterns.

__

Performing The Smart Nation

How have your studies in digital filmmaking — a medium that parallels the rise of digital art — influenced the way you approach your work now?

Digital filmmaking and digital art are indeed intertwined. I’m thinking about the transition from analog to digital film, allowing for individuals to gain access to digital imaging tools at an affordable rate, and hence creating works that challenge the dominant media and discourses at that time — diversifying conversations.

Presently, with ubiquitous smart devices, online platforms for production and distribution, we can safely say that many have the means to digital production, and these forms of production have far-reaching effects on how we view ourselves.

With social media, everyone is a cinematographer, framing their bodies, performing their identities, and the content that we make interacts with a vast digital network of images and relations. Leaning more towards experimental filmmaking and its history of rethinking cinema, questioning the dominant media, and pushing new technologies to its breaking point are all methodologies that I bring into my work.

As an art educator, I’m currently challenging my students to look beyond the moving images we see on the screen, and instead, to observe the underlying algorithms and processes that take place behind its surface.

__

Ryan Benjamin Lee — Visual Artist

In recent months, “traditional” art has been forcefully moved online due to the mass closure of galleries and museums worldwide — artists, who were once trained in other mediums have gathered to use “digital art” as a new media for expression. As a digital artist who has explored the likings of this medium for a while, what are your thoughts on the trend and are you receptive to this change?

I do think artists are doing everything that they can online.

However, digital art, for all its merits, does not work for everyone. I think the digital sphere can make some people incredibly unhinged (like me) and that can be incredibly liberating, but for others, a piece of yourself can be chipped off online.

Some things don’t translate well online, and I think that’s fine. I don’t think all my work is made to shown on a laptop either. I make work for iPhones and cinemas, Vimeo and museums.

The beauty of digital art is its ability to permeate all these different spaces, and if an artist can wield that to their advantage then that’s fantastic!

__

Untitled (Starry Bodies)

How else do you think institutions (e.g governing bodies, galleries and educators could better perceive and acknowledge the value of digital art?

I love what museums like the Indian Heritage Centre are doing on IG, where they task different people to dress up and reinterpret their collection. It’s such a great way for people to have fun and be silly in a non-white cube setting, while still engaging with art. And people go hard! I think we should start conflating contemporary art forms as heritage. It is every person’s right to have free access to their heritage, not dissimilar to museums.

They are people’s histories, we can demand these things.

The National Film Board of Canada famously puts its archives online for free access and has been releasing more work since the coronavirus outbreak. Canada has a rich independent animation scene because it saw the value in immigrant and indigenous stories way back in the 1960s and created pathways for people to become professional animators and educators — it’s pretty self-sustaining.

I’d recommend browsing their catalog if you’re interested in experimental documentary or independent animation. Alternatively, on a ground level, an amazing thing that the online animation community has been doing during this period is releasing their films on Vimeo for free. Usually, you’d keep your videos private until your festival run has ended.

But now with the current climate and so many film festivals being cancelled or streaming, it just doesn’t make sense anymore. I’ve been bingeing Vimeo accounts from my favourite animators. I’d recommend Annapurna Kumar’s Something to Treasure, Brin Gordon’s Part I: Stonehenge, and Jodie Mack’s The Great Bizarre (which is on Mubi).

__

Scream

Sampling seems to be the process you often use — to the uninitiated, the intentional assembly of various fragmented forms has often been criticised as an invaluable process of art creation by traditionalists and a remark that digital art is often afflicted with, is that an issue with the way you work?

I’m a full believer and lover of sampling. I think when sampling is at its best, it adds value to what came before it. It should not be wholesale mimicry or nostalgia. I’d turn people on to some good Hip- hop producers and breakers. Sometimes I’ll listen to an early 1960s or 1970s bangers realising that I’d heard it in a Kanye song before (aka Chaka Khan) or a Shaw Brothers martial arts choreography that I recognise as a hip-hop move.

It’s strange how these things show themselves in unexpected ways.

Personally, I love to try and trace the lineage of a song. My favourite musical lineage is Vampire Weekend’s Step in the 2010s, which they sampled lyrics from Soul of Mischief’s Step To My Girl in the 1990s, which in turn sampled a saxophone cover of Bread’s Aubrey. I first heard Aubrey when I was in primary school cause my dad is such a fan of the early 1970s soft rock.

Listening to all these tracks back to back is so exciting because they allow disparate musical genres to interact in such bizarre ways while having the past haunt contemporary art.

__

Untitled (Starry Bodies)

The rise of digital art is often compared to photography and film, where we pay for the privilege of access rather than ownership — considering how moving images is a focus of your artistry, do you think the consumption of digital art parallels this and how else do you think we could consume it?

I think a lot about my access to resources and software. Firstly, I think about the institutionalisation of animation in Singapore and how it’s still at very early stages compared to where photography is now. Even when software has been more accessible than ever, digital art still demands a lot of resources.

For example, in an ideal world, a person’s early access to animation in Singapore would be through education, possibly an integrated media program taught with non-animation centric tools like Photoshop. It’s a Swiss army knife tool that can be used in situations beyond art.

Even if you’re a designer or marketing strategist you would need these skills. I also have wild dreams of teaching free animation courses or conduct animation residencies for artists. Free education to further de-centre these skillsets from institutions and allowing it to proliferate in other art forms and to people who cannot afford to pay for access.

I’d be like a technician in a ceramics workshop, but for software. It’s also about making technology feel welcoming, which I think is the toughest job for any person teaching media.

But for now, I try to share whatever knowledge I have access to.

__

Clara Lim — Visual Artist

In recent months, “traditional” art has been forcefully moved online due to the mass closure of galleries and museums worldwide — artists, who were once trained in other mediums have gathered to use “digital art” as a new media for expression. As a digital artist who has explored the likings of this medium for a while, what are your thoughts on the trend and are you receptive to this change?

Rather than being receptive, I think we have to be very adaptive to changes in formats of consuming art. It also goes to show that you don’t always have to go back to what you are trained for. I strive best around a community of creatives and I think human interaction is something that cannot be moved online. That is still something that I am trying to overcome or think about most in these transitions of media – humanity.

__

You’ve practiced digital art throughout your time at Nanyang Technology University School Of Art, Design and Media, was it a common media to explore in school, and were there any challenges and/or stigmas to your perusal of digital art.

I belong in the last and final batch where our majors were split into six very specific pathways of Animation, Film, Interactive Media, Photography Product Design and Visual Communication. These pathways in some forms live in both digital and analog formats of presentation. We were very much given the freedom to pursue our preferred formats, albeit being given talks about the priority of being commercially viable.

The element of art was credited to the Art History modules at the start of my freshman year. I find them to be extremely enriching and it has shaped quite a bit of my vernacular in the expression of my work.

You will always face stigmas as a creative, beliefs that our work is easy to accomplish, that we will not be able to earn a wealthy living, all that comes along with hypocritical talks of thinking creatively while art and design are found in almost every crevice of the world.

__

We’re Good

How else do you think institutions (e.g governing bodies, galleries and educators could better perceive and acknowledge the value of digital art?

I am generally still very apprehensive about institutions, so I cannot speak about this with the utmost confidence. Digital art should not be collected or commissioned for its face value, gadgetry and aesthetic. In a very crude way, do not consume Nam June Paik’s work just because it’s cool and iconic but because of how he uses technology to look closer into humanity and modes of communication. C

uratorialship needs to come through. Otherwise, consumption of digital art on its own is very diluted, and we already have social media to thank for that. I think digital art has always been present since the sixties so it is not very revolutionary.

I just want people to isolate themselves away from technology in digital art and question the current chosen methods of presentation. Work presented on an iMac G3 isn’t just retro or nostalgic, it presents the icon of computing. It’s the same fashion in how Arduino boards and circuity used for easier data collection in inaccessible areas are often seen on the white walls of galleries because those very elements are the general public’s first instinct when it comes to digital art in the late 2010s.

I find it very ironic to be commissioning art that uses technology to commentate on issues of climate change and Anthropocene.

__

Value is a topic you’ve explored in your 2019 installation, We’re Good; a commentary on social discourse and throwaway culture — how do you perceive value as an artist and a designer, and how does it influence the way you approach your works?

We live in a world that has space for different explorations of art. I am not a fan of mindless art unless it is cathartic and you are healing yourself while making said art. The value of my art lies in reconciling the issues in our lives, reconnecting with my parents and their upbringing, and how it has trickled down onto them while raising me as a child.

I have come to realise that they have played a huge role in influencing my works as they lived through decades of public policies. Eventually, I would live through historical points of my own life, just like how this COVID-19 situation is very much part of our lifetime and history.

__

We’re Good

Most, if not all, of your materials, are gathered digitally from stock images and found media — do you think an approach like this would deflate the value of your works in comparison to how traditional art is made, and how do think it could be appropriately appreciated?

Definitely! I always get devalued and shaded for, simply because of not wanting to replicate existing outputs of work. I believe in learning, but I do not agree with over-glorifying the act of making. People are obsessed with trying to learn the next cool skill and thinking they can do things themselves rather than to collaborate.

You end up spending a good afternoon struggling, only to have an Instagram post when Beeple (an industry god) has put up a great deal of his work online as an open source for you to build on top of.

This can be very iffy and grey because people perceive that as copying and worse, plagiarism. I do draw the line, as I think plagiarism is wrong because you’re using another person’s work and passing it off as your own. Whereas copying with the due credits and citing of inspiration, without commercialisation, is very much acceptable.

This is especially so in an Asian context where copying has never been villianise, unlike western culture.

I think because of copyright laws, most works get stuck in this very grey area of probability for talks about sales. I have learned to slowly navigate around this through a heavy transformative presentation through my works. I think the art of remixing works can be appropriately appreciated when you can feel the gratitude and influence another artist have on each other.

It has the potential to create a wholesome reactive ripple in a community.

__

This story first appeared in the May ’20 issue of Men’s Folio Singapore.